How Model Railroad Train Track Currents Work

Most model trains run on low voltage. Unlike the AC electrical circuit in your house, the electricity that moves your locos is DC, i.e. Direct Current. The supply to your layout comes by plugging a power pack (also called a transformer) into a wall socket that takes the AC supply, steps it down to the 12-15 volts needed to run the trains.

© Copyright https://www.modelbuildings.org All rights reserved.

The transformer converts the output to DC, filters the DC to purify it, then outputs the supply from the terminals on the back of your controller, along a couple of wires to the tracks where it is picked up by your locomotives wheels, turning the motor within. The throttle control varies the voltage to the rails, changing the speed of the motor and consequently the rate your locomotive moves down the track.

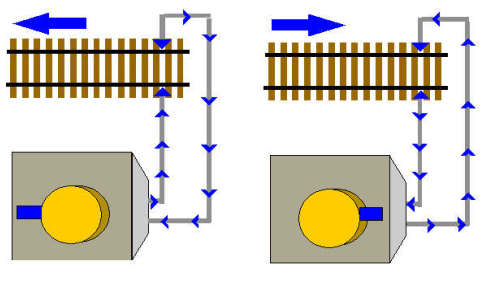

DC electricity is directional, so the electricity flows along the wires in a certain direction, and the locomotive moves in the direction set by the directional switch on your controller (or left and right if your controller has a center off type control knob).

These lower step-down voltages are not usually dangerous, but it’s safest to attach wires to the terminals when the power pack is unplugged from the wall.

Regardless of how simple or complex the layout is; all model train operation follows one basic principle. You control the train speed and direction by varying the voltage and polarity of the electricity reaching the motor. You are in control!

Electrical currents are not the same in every country. It is important that you know what voltage system operates in the country where you reside. If you are at all unsure, contact your local electricity supplier, or a local electrical contractor. The high voltage circuit in the wall socket can cause injury or death. Also, carefully read any safety instructions that are included with most train sets before getting started.

Virtually all the equipment in the model railroading hobby is electrically powered. Although Lionel “O” scale and American Flyer “S” scale trains are powered by alternating current transformers, nearly all other scales are powered by direct current power packs. This is a good thing to keep in mind if you are looking for a used bargain. It is not healthy for your locomotives and accessories to try to deal with the wrong type of power.

Most power packs have two outputs. One output is a variable voltage that powers the locomotives, typically from 0-12 VDC. The variable voltage operates the motor or motors and the lights in the locomotive, and the amount of voltage determines locomotive speed. The other output is a constant 12 VDC, which is used to run accessories such as switch machines, block signaling, and lighting.

Each power pack has a current rating as well. The amount of current the power pack can supply translates roughly to the number of locomotives it can simultaneously power. A typical HO scale locomotive will draw around one-half an ampere of current under load, so you can use this rule of thumb to purchase the appropriate sized power pack for your layout.

Boxed train sets at one time included a small power pack sufficient to run the locomotive, but the more recent trend has been to only supply locomotive and rolling stock in boxed sets, with the power pack choice left up to the purchaser. If you are buying a boxed set, be sure to verify that the power pack is not included and plan to purchase one.

If you stay interested in the hobby beyond the boxed train set stage, you will soon be thinking of acquiring more locomotives. When you get to the point of running more than one train, the next consideration should be how to throttle them. If you just put the second locomotive on the same track as the first, you’ll find that the power pack throttle is in control of both. Unless you wish to operate this way (very inconvenient!), you’ll want to devise some method of individual throttle control.

In the earlier days of model railroading, this was done by dividing the layout into power blocks with switches to control the voltage and a throttle arrangement for each block to operate the trains. This method becomes cumbersome very quickly, since any changes to the electrical arrangement can lead to extensive rewiring of much of the layout.

DCC Versatility

The development of computer chips came to the rescue some years ago. Now days, the Digital Command and Control, or DCC, system allows individual control of locomotives with relative ease. A command transmitter device is attached to the rails, and each locomotive has a command receiver and motor/light control unit inside that interprets throttle and accessory commands from the transmitter, and sets the motor speed and light and/or sound condition accordingly. Digital Command Control (DCC) gives you a digital edge in the functioning of locomotives along a model railroad. It helps multiple locomotives to move on and occupy the same electrical section of the track.

This increases the functionality and enables you to manage more trains on the model railroad at once. Furthermore, it can also control the additional requirements of the track, including the dimming and powering of headlights, marker lights and the sounds.

As opposed to conventional DC systems that use direct current to provide power to each locomotive, DCC uses signals that are transmitted along the track. The digital controller connected to the track supplies the power and control signals to all the locomotives along the track.

Each locomotive is fitted with its own decoder that powers up its motor and automatically controls its direction, lighting and even sound. All the locomotives are thus electrically independent of each other and do not need to be powered up separately.

No, there is no need to replace your existing track model or layout in order to work with DCC. The only consideration you need to take is that the track is clean and intrusion free at all times. Extra isolated sections, switches or loops may also cause interruption; therefore, it maybe a good idea to have a single live circuit.